Confronting Prejudice: How to Protect Yourself and Help Others

Dealing with prejudice—whether it’s microaggressions, bias, or discrimination—is physically and psychologically demanding. But avoiding it is not always an option.

“Not everyone has the luxury of leaving a prejudicial workplace or neighborhood,” said Natasha Thapar-Olmos, PhD, Program Director at OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the online Master of Arts in Psychology at Pepperdine University’s Graduate School of Education and Psychology. “But there might be things we can do and some tools to cope.”

What are those tools? Use this guide to understand where prejudice comes from, what it looks like, and how you can help others experiencing it.

What Is Prejudice?

Word choice matters. We often use words like prejudice, bias, and bigotry interchangeably, and there are aspects to each of these concepts that overlap. But when addressing prejudice, it’s important to understand some of the subtle distinctions.

To understand prejudice, we also need to understand stereotypes. A stereotype is an oversimplified and widely held standardized idea used to describe a person or group. A form of social categorization, stereotypes are a shortcut for the brain when grouping information. Categories of stereotypes include:

Positive Stereotypes

Beliefs perceived as favorable qualities for a group.

Helpful Stereotypes

Beliefs that assist people in rapidly responding to situations that are similar to past experiences.

Negative Stereotypes

Beliefs perceived as unfavorable qualities for a group.

Harmful Stereotypes

Beliefs that spur people to respond unfairly or incorrectly to situations because of their perceived similarity to past experiences.

Remember that positive stereotypes are not always helpful, and helpful stereotypes are not always accurate.

Stereotypes can help lay the foundation for prejudice—a preconceived, unfair judgement toward a person, group, or identity. Prejudice is formed without sufficient evidence or reason and can be based on qualities such as these:

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Nationality

- Gender

- Sexuality

- Religion

- Disability

- Class

- Age

Prejudice can dictate how people treat each other, resulting in any of the following:

Bias: an inclination, tendency, or particular perspective toward something; can be favorable or unfavorable. When bias occurs outside of the perceiver’s awareness, it is classified as implicit bias.

Microaggressions: an indirect, subtle, or unintentional comment or action that is prejudicial toward a marginalized group.

Bigotry: the intolerance of different opinions, beliefs, or ways of life.

Hate: disgust or contempt for another group that facilitates a desire for separation, strong emotions of fear or anger, and dehumanizing beliefs. Hate can take the form of:

- Hate Speech: form of expression intended to attack or incite hatred of a class of persons.

- Hate Crime: criminal offense motivated by a bias.

- Hate Group: organization that attacks or condemns a class of people.

Discrimination: unfair and negative treatment different categories of people or things, especially on the grounds of race, age, or sex.

Oppression: a cruel and unjust abuse of power that prevents people from having opportunities and freedom.

Although acts of hate can be a result of prejudice, prejudice does not require hate. Engaging in sexist behavior, for example, does not require an individual to be a misogynist. Prejudiced behavior can’t simply be viewed through the lens of interpersonal interactions; it must also be understood at an institutional and societal level. For example, anyone can be prejudiced against a person of another race. But understanding racism necessitates acknowledging who has historically been marginalized, who is privileged, and what power dynamics exist.

Who Experiences Prejudice?

According to a 2019 Pew Research Center Race in America survey, three-quarters of black and Asian respondents and more than half of Hispanic respondents reported experiencing discrimination or being treated unfairly because of their race. Black respondents consistently reported being most likely to experience unfair treatment such as being treated suspiciously, being treated as unintelligent, being treated unfairly at work, being stopped unfairly by police, and fearing for their personal safety. Asian respondents were most likely to have been subject to racial slurs.

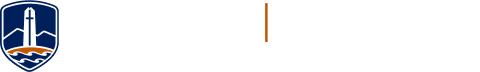

Most adults acknowledge the difficulties with discrimination and prejudice that marginalized groups face in the United States. A separate 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that 82% of respondents surveyed believed that Muslims experienced at least some discrimination, followed by Blacks (80%), Hispanics (76%), and gays and lesbians (75%).

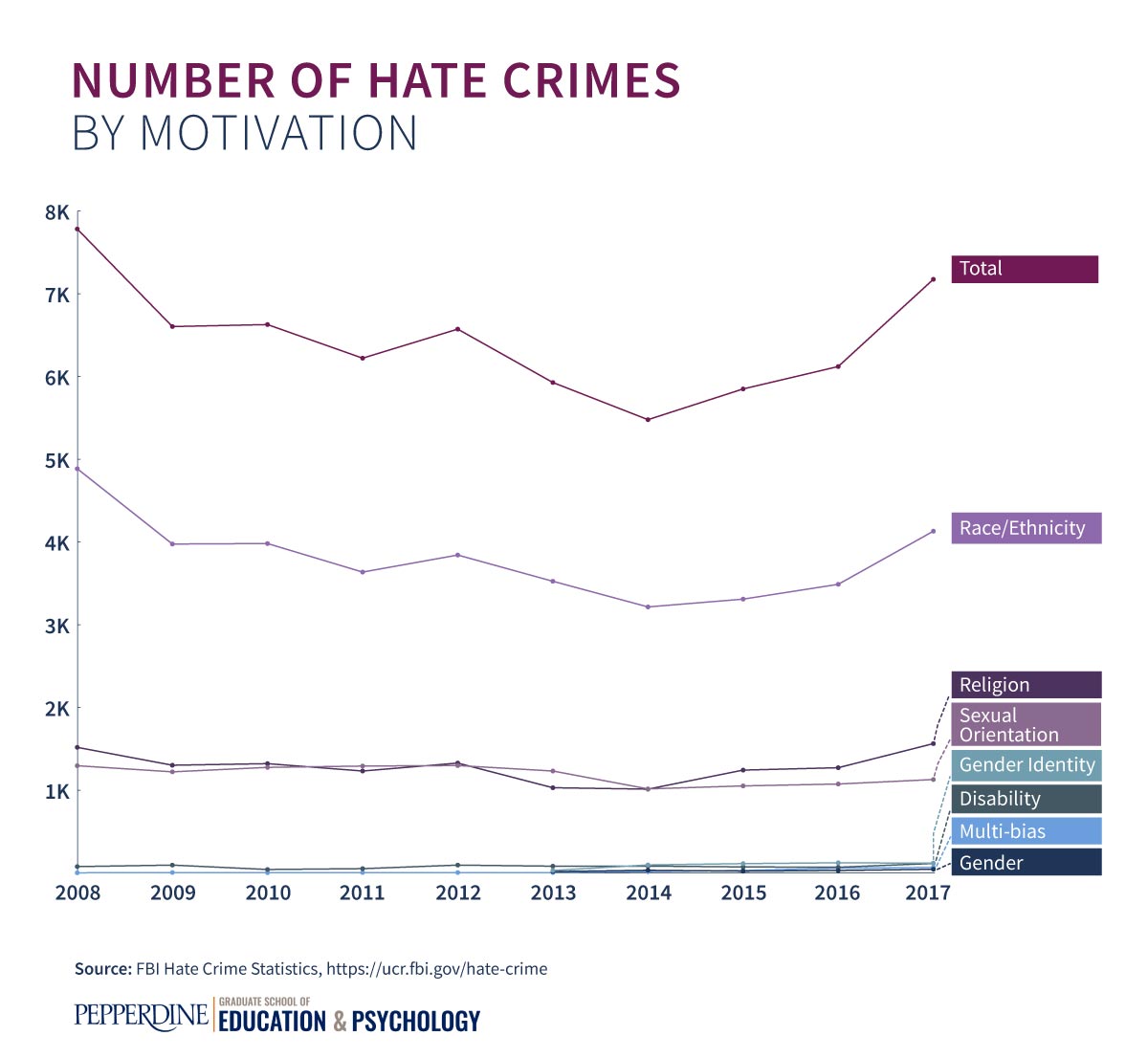

According to the FBI’s hate crime statistics, there were 7,175 criminal incidents motivated by bias toward race, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender, and gender identity in 2017—17% more than 2016. Out of all of those incidents, nearly three out of five were motivated by race and ethnicity.

Elissa Buxbaum, director of campus affairs for the Anti-Defamation League, said they’ve noticed the trend, too. However, she points out that increases can be attributed to a few different things.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that more incidents were happening,” she said. “But it does mean that more people were reporting it and that more people were feeling comfortable to report.”

What Are the Health Effects of Prejudice?

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the environmental factors that contribute to the well-being of communities and individuals. Some examples of such influences include access to educational opportunities, exposure to crime, and transportation options.

Prejudice is intertwined with these variables; structural discrimination disadvantages less privileged groups and affects resource allocation, opportunities, and socioeconomic stability. For example, incarceration rates are higher for minorities and schools are becoming more racially segregated—contributing to feelings of safety, funding, and security.

African American men living in poverty are almost three times as likely to die early than those living above the poverty line, according to a JAMA study on race and poverty as a risk. There is no difference for white men in and out of poverty.

On the individual level, prejudice can have direct health consequences. Just the anticipation of prejudice or discrimination can lead to cardiovascular and psychological stress responses, according to a 2011 AJPA study on discrimination and stress. Over time this can contribute to depression, anxiety and feelings of isolation or loneliness.

It can also lead to self-stigmatization.

“People of marginalized or discriminated groups can develop negative beliefs towards themselves,” Thapar-Olmos said. “That gets in the way of all kinds of things—relationships, functioning, recovery.”

How Can You Build Resilience Against Prejudice?

It is never your responsibility to educate someone who is hateful or discriminatory toward you.

Combating prejudice is the oxygen mask on an airplane, Thapar-Olmos explained. If you’re traveling with someone who requires assistance, place your own mask on first before helping the person next to you.

“If we’re not healthy and we’re not monitoring our own emotional reserves, then we’re not doing anyone else any favors,” she said. Thapar-Olmos recommends the framework below to start building internal resilience against prejudice and discrimination.

- Face reality head-on. Denial can be powerful. Name and acknowledge your experiences, whether it is to a family member, friend, or counselor.

- Make meaning out of experiences. How can we learn from these experiences? How can they inform us? “I think a lot of people find meaning in growing from pain by enriching others,” Thapar-Olmos said.

- Control what you can. You may not be able to change other people, but what do you have control over? How can you structure your interactions? What are some healthy outlets you can use? Exercise agency whenever possible.

How Can You Help Others Who Experience Prejudice?

While it’s important to put your own mask on first, there are instances where you will be called to step in when others are the victims of prejudice.

Listen and Validate

If a friend comes to you with a story about their experience with prejudice or discrimination, it’s natural to want to help or fix the situation. But there are some things you should do before trying to spring into action.

Listen to their story. Stop everything else and take time to let them talk. Interrupting or jumping to conclusions, even with the best of intentions, isn’t helpful. Practice active listening and ask questions, paraphrase back, and watch for non-verbal cues.

Validate their experience. In situations of prejudice, there can be a lot of unknowns: What was the intent? Do they realize what they said? Uncertainty can make it easy for people to feel like it’s all in their head or they’re making it up. Validation is not blind agreement; it helps you understand someone’s response through their lens. It is saying, “I understand why you feel this way, based on who you are, what your history is, and what your experiences have been.”

Intervene in the Moment

If you witness an act of prejudice happening, there are ways you can act in the moment. The 4 Ds of bystander intervention are often used to address instances of sexual harassment or assault but can be applied for all kinds of scenarios.

Direct: Step in and address what’s happening directly. The direct method can be simple and effective, but it can also be uncomfortable or seem confrontational. Sometimes, this works better if you have a relationship with one or all of the people involved. Only intervene directly if you feel safe. Try saying:

- Hey, what you’re saying isn’t okay. Please stop.

- Leave them alone.

- This isn’t appropriate. You should walk away.

Distract: Sidetrack either person with a new conversation, question, or activity. This is a more casual method than Direct, but can still be effective. Try saying:

- Excuse me, will you show me where the bathroom is?

- Did you see the game today? I can’t believe we lost.

- We’re going to grab lunch. Come join us!

Delegate: Find someone who can help. Whether it’s a friend of yours, or a friend of theirs, having some backup can make you feel more comfortable to address the situation. Try saying:

- That woman looks uncomfortable. Can you distract the guy she’s talking to so I can check with her?

- Do you know him? I think he needs some help.

- I think something is going on, but I don’t know what to do. Will you help me?

Delay: Check in with the person later. Sometimes, you may not feel comfortable or safe intervening in the moment. When that happens, reach out when you can and see how you can help. Try saying:

- Are you okay? I saw what happened back there.

- Can I help you out of this situation?

- Do you know her? I heard what she said to you and wanted to check in.

Be an Ally, Advocate, and Activist

Thapar-Olmos recommends finding agency and voice where you feel comfortable. Identify ways you can support, speak, and act on behalf of causes and people you care about. Allyship, advocacy, and activism are not mutually exclusive for any person or act.

Allyship is support for a particular group, especially a marginalized group that you are not a member of.

Advocacy is public support for a cause or movement

Activism is action for social or political change in the form of campaigning, protesting, and the like.

Everyone can still be surprised by their own biases, and that can make people feel vulnerable or defensive. But people need to push through that reaction.

“There’s no end point. It’s not like you ever fully eliminate bias,” Thapar-Olmos said. “But I think we have to be willing to engage in the discomfort if we’re going to talk about it and try to help other people.”

The following section includes tabular data from the graphics in the post above.

How Prevalent Is Discrimination Among Racial and Ethnic Groups?↑

| Racial or ethnic group | Percentage Personally Experienced Discrimination |

|---|---|

Black | 76 |

Asian | 76 |

Hispanic | 58 |

White | 33 |

Source: Pew Research Center, April 2019, “Race in America 2019.”

Which Demographic Group Does the Public Believe Is Most Likely to Experience Discrimination?↑

| Racial or ethnic group | Percentage of Respondents |

|---|---|

Muslim | 82 |

Black | 80 |

Hispanic | 76 |

Gay and lesbian | 75 |

Female | 69 |

Jewish | 64 |

Evangelical Christian | 50 |

White | 50 |

Male | 39 |

Source: Pew Research Center, April 2019, “Sharp Rise in Share of Americans Saying Jews Face Discrimination.”

What Motivates Hate Crimes in the United States?↑

Number of Hate Crimes by Motivation

| Year | Race/Ethnicity | Gender Identity | Gender | Disability | Sexual Orientation | Multi-bias | Religion | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2008 | 4886 | N/A | N/A | 78 | 1297 | 1519 | 3 | 7783 |

2009 | 3976 | N/A | N/A | 96 | 1223 | 1303 | 6 | 6604 |

2010 | 3982 | N/A | N/A | 43 | 1277 | 1322 | 4 | 6628 |

2011 | 3637 | N/A | N/A | 53 | 1293 | 1233 | 6 | 6222 |

2012 | 3843 | N/A | N/A | 96 | 1299 | 1329 | 6 | 6573 |

2013 | 3526 | 31 | 18 | 83 | 1233 | 1031 | 6 | 5928 |

2014 | 3216 | 98 | 33 | 84 | 1017 | 1014 | 17 | 5479 |

2015 | 3216 | 114 | 23 | 74 | 1053 | 1244 | 32 | 5850 |

2016 | 3489 | 124 | 31 | 70 | 1076 | 1273 | 58 | 6121 |

2017 | 4131 | 119 | 46 | 116 | 1130 | 1564 | 69 | 7175 |

Source: FBI Hate Crime Statistics.

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the Online Master of Psychology program from Pepperdine University.