Looking Beyond Hypermasculinity to Address Domestic Violence in Communities of Color

When Caminar Latino opened its doors in 1990, the Atlanta-based organization’s primary tactic to help survivors of domestic violence was to encourage women to leave their abusive partners. But as time passed, the organization realized that shifting control over survivors’ choices from their partners to professionals didn’t give women the power to determine their path forward.

“When we really started working in partnership and listening to what women felt was best for them, we realized that they were a lot more knowledgeable about what their next steps should be,” said Jessica Nunan, executive director of Caminar Latino.

Instead of counting separation from a partner as a win, the group reexamined the dynamics of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the Latino community and discovered it is an issue that affects entire families. Emphasizing the importance of family among Latinos, who often have tight-knit intergenerational relationships, could help them create effective strategies for preventing abuse.

“We looked at different cultural values and recognized that there were some parts about the Latino culture which we needed to support and other parts that we didn’t really need to pass on to the next generation,” Nunan said.

“We looked at different cultural values and recognized that there were some parts about the Latino culture which we needed to support and other parts that we didn’t really need to pass on to the next generation,” Nunan said.

When working with communities of color affected by IPV, culture can often be viewed as a barrier to successful intervention. But integrating strong positive cultural values into treatment can create more responsive interventions that better address the unique needs of survivors and prevent partners from engaging in abuse.

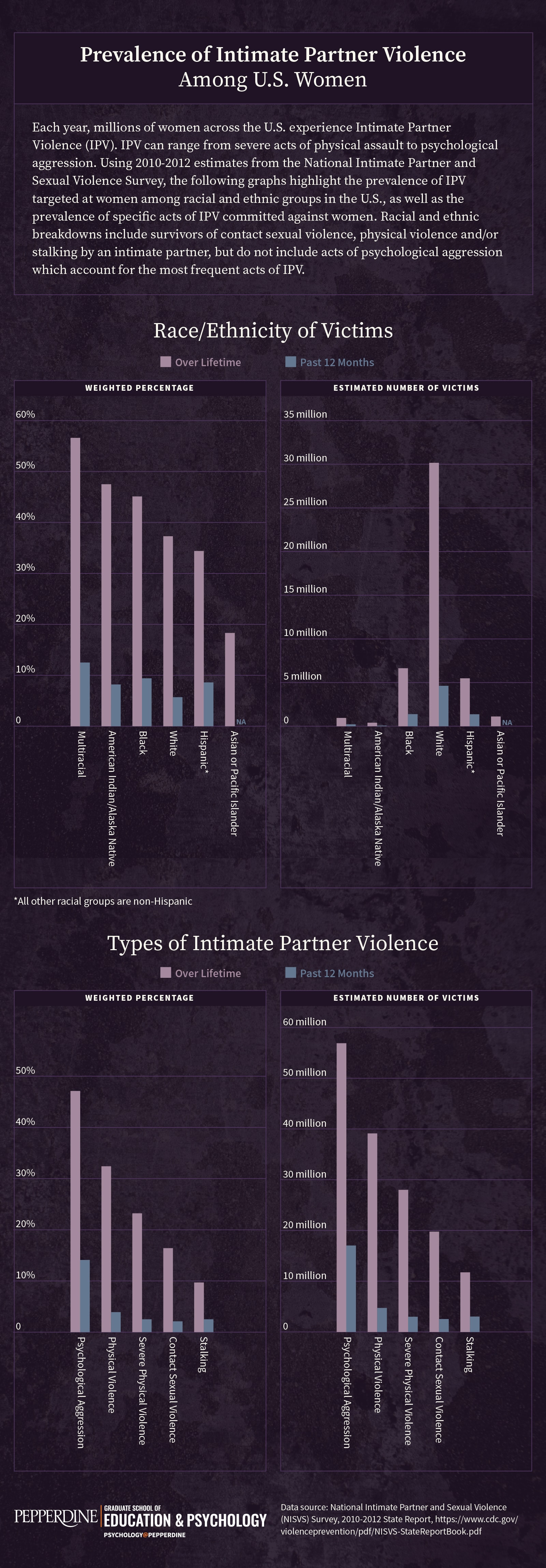

Misconceptions about Race and Ethnicity

According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, approximately 6.6 percent of U.S. women reported experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence or stalking over a 12 month period during 2010 to 2012. When accounting for their overall lifetimes, that number jumped to 37.3 percent. Multiracial women reported the highest rates of violence over the past year at 12.5 percent, followed by blacks (9.4 percent), Hispanics (8.6 percent), American Indians (8.2 percent), and whites (5.7 percent).

Read the text-only version of the infographic here.

Although statistics suggest that communities of color are more likely to engage in IPV, experts warn many studies do not accurately capture the reality of the problem. On one hand, many survivors may be wary of seeking help.

“In communities of color, there is already a cultural phenomenon of not revealing personal matters or private matters and also not trusting those that might be able to provide assistance,” said Ruth Glenn, executive director of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. “There is a particular element of not being believed by those in authority.”

And on the other hand, black and Latino communities are more heavily policed.

Lee Giordano works as director of training at Men Stopping Violence, a Georgia-based organization that provides trainings and programing aimed at preventing violence against women. Giordano noted that about half of the men who enter his programs come through the criminal justice system. Those men tend to be men of color. The other half come through a referral program from therapists and faith communities and includes many more white men.

“Often how we identify perpetrators of intimate partner violence is through the criminal legal system,” Giordano said. “If you looked at the statistics closely, men of color and white men commit acts of violence at pretty similar rates, but the men who get caught because of inequities in the justice system are more likely to be men of color.”

Although hypermasculinity and male dominance can sometimes be associated with communities of color, Giordano argued that U.S. culture as a whole is organized in a patriarchal structure. That structure places a higher value on masculinity over femininity and promotes gender norms that drive IPV, which is rooted in a need for control.

“In mainstream white American culture, there are messages that say men should be in control, should dominate women, should be heads of households, and should have rights to make big decisions, to control the finances, and to dictate family norms,” Giordano said.

These cultural norms, in conjunction with the way society tells men what emotions are acceptable to show, help perpetuate the use of violence and intimidation, said Dr. Miguel Gallardo, professor of psychology at Pepperdine University’s Graduate School of Education and Psychology (GSEP) and faculty member at OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine.

“We are still sending messages to young boys and men not to express certain emotions because it’s a sign of weakness,” said Gallardo.

“We are still sending messages to young boys and men not to express certain emotions because it’s a sign of weakness,” said Gallardo, who also serves as director of Aliento, The Center for Latina/o Communities at GSEP. “Because we don’t learn how to express a range of emotions, depression can often come out as anger, despair, resentment or animosity.”

Both men and women who don’t learn to effectively express emotion can resort to harmful behaviors when dealing with stressful or overwhelming situations, he added. And, many men who experience this type of intimidation or abuse growing up resort to the same behaviors to exert control.

Overcoming Cultural Hurdles

Still, Gallardo acknowledged that there are distinct challenges when it comes to addressing IPV in communities of color. While many people like to point to concepts such as machismo — a strong sense of masculine pride often attributed to Hispanic men — as a driving factor in the Latino community, Gallardo said that explaining IPV through that lens is simplistic and disregards historical, social and economic factors.

“We have to be careful about using culture to make sense out of maladaptive behaviors because there are a lot factors that contribute to the way we respond and find ourselves living our lives,” Gallardo said.

He pointed out that many Latino and black people in the United States live in struggling communities with limited resources and opportunities to move up the economic ladder. Institutionalized racism, not just within the criminal justice system, but in the broader context of their everyday lives has negative social and emotional consequences. The environments in which these communities live are higher stress and families are simultaneously “more exposed and vulnerable to society’s judgments, perceptions and misconceptions,” Gallardo added.

Nunan, who primarily works with Latino families, said that immigration policies are also a barrier to addressing IPV. In February and March of this year, Caminar Latino saw a drop off in the number of people attending its programs. When advocates called to ask why people were no longer coming, they pointed to the change in the presidential administration.

“There is a lot of fear in terms of asking for help,” Nunan said.

And simply helping survivors understand these behaviors can be criminal and that they can ask for help can be a challenge. Nunan noted that different countries have different laws relating to domestic violence which don’t necessarily cover the broad spectrum of abusive behavior that should be included under IPV. Expanding people’s understanding of violence against women beyond the most severe forms of abuse is an important aspect of addressing IPV, advocates said.

For example, most of the survivors Glenn worked with said that emotional and psychological abuse were often the most devastating to endure, and that there are a number of other ways partners can act out controlling behaviors.

“We know of survivors who have had their medication held back so that they couldn’t operate normally,” Glenn said. “We’ve had survivors talk about not being able to access funds or money to live appropriately. The list goes on and on.”

Emphasizing Positive Values

To address IPV in Latino communities, Caminar Latino first recognized that a significant amount of the families interacting with the organization that experienced violence in the household stayed together regardless of interventions. Addressing IPV required developing services for every family member.

For women and children, who are more likely to be survivors, Caminar Latino offers support and reflection groups, individual counseling, legal assistance and connections to resources such as shelters. The group also emphasizes education on the spectrum of domestic violence, survivors’ legal rights, and healthy relationships.

For men, who often make up the group engaging in violent behaviors, the organization’s programs focus on developing a better understanding of the behaviors that fall under the umbrella of domestic violence and the effects of those behaviors. They hold men accountable for their actions and do not allow them to fall back on excuses such as drinking or childhood experiences with violence. The organization uses the cultural importance placed on family as a way to encourage them to stop engaging in violent behaviors.

“Instead of bringing it to a place of ‘Don’t use violence because you’re going to get arrested,’ we say, ‘How did it feel when you saw your father use violence against your mom? You want to be a good father, but how does that line up with you hurting your child’s mom?’ ” Nunan said.

Nunan noted that treating men with respect and highlighting the valuable components that they bring to their family, such as serving as a provider, help men see the program as something beneficial, rather than a punishment. Caminar Latino reported that three-quarters of men finished its program and 90 percent of families with a man in the program reported that physical violence stopped within two weeks of entering the program.

These results are consistent with the research that Gallardo’s students have done on the issue, which found that Latino men who engaged in IPV still reported being highly committed to being good fathers, good husbands and good providers.

Calling on Communities to Help

To better help families, Gallardo also believes that advocates must engage at a community level.

“The one limitation sometimes with individual therapy is that in some ways it unintentionally reinforces this notion that the problem solely resides within the individual,” he noted. “And while that’s true in some cases, there are some situations where the context in which people have found themselves has a lot to do with how they have learned to respond to problems in their lives and their relationships.”

Abusive men who have gone through intervention programs returning to communities that support abusive or controlling behaviors is a difficult problem to address, Giordano added.

To help create change outside of the home, his organization Men Stopping Violence requires men who enter program through the justice system and through referrals to bring other men from their communities into the process.

For example, during each participant’s mid-term review, men are required to review and report their pattern of abuse in front of their class. They must bring in somebody from their community network who can hold them accountable both in the moment and moving forward. Participants are also required to create a community project based on something that they have learned within the program that they then share with at least four other men in their community.

“Responsibility for the prevalence of violence against women lies with the individual perpetrator in addition to the community,” said Giordano.

“The program is designed to disrupt the distinction between the individual perpetrator as solely responsible,” said Giordano. “Responsibility for the prevalence of violence against women lies with the individual perpetrator in addition to the community.”

The success of programs at organizations like Men Stopping Violence and Caminar Latino offer hope for advocates. But Glenn is still amazed at how little has changed regarding the amount of survivors coming forward each day.

“I couldn’t do my job if I didn’t think abusers had the ability to change,” Glenn said. “I believe that what they do is a conscious choice and what that means is that they can change. Unfortunately, we haven’t done enough as a society of addressing what it is that drives them.”

If you or somebody you know needs help, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 or 1-800-787-3224. The 24-hour hotline is both anonymous and confidential. For further resources on how to obtain help or spot the signs of abuse, please visit the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the online clinical psychology master’s program from Pepperdine University.