Navigating Family Life after a Suicide Attempt

When Dior Vargas was a girl, she tried to take her own life more than once by overdosing on pills.

“I was being made fun of a lot in school. There was this one girl who was so mean. She was really, really cruel. I was having a lot of problems at home. It had been like that for years,” Vargas told LiveThroughThis.org, a site that features the stories of dozens of suicide attempt survivors, many of whom say they thought about or attempted suicide at a young age.

Bullying, trauma and abuse are often the backdrop to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts by children and teens, say experts, who are increasingly alarmed by the growing numbers of children who’ve considered or tried to end their own lives.

From 2000 to 2016, suicide rates in the U.S. have steadily increased. Suicide attempt rates are also climbing among children. From 2008 to 2015, emergency room and hospital visits linked to suicidal thoughts and attempts across 31 children’s hospitals in the U.S. more than doubled, with the largest increases among youth 15 to 17, according to a 2018 study in the journal Pediatrics.

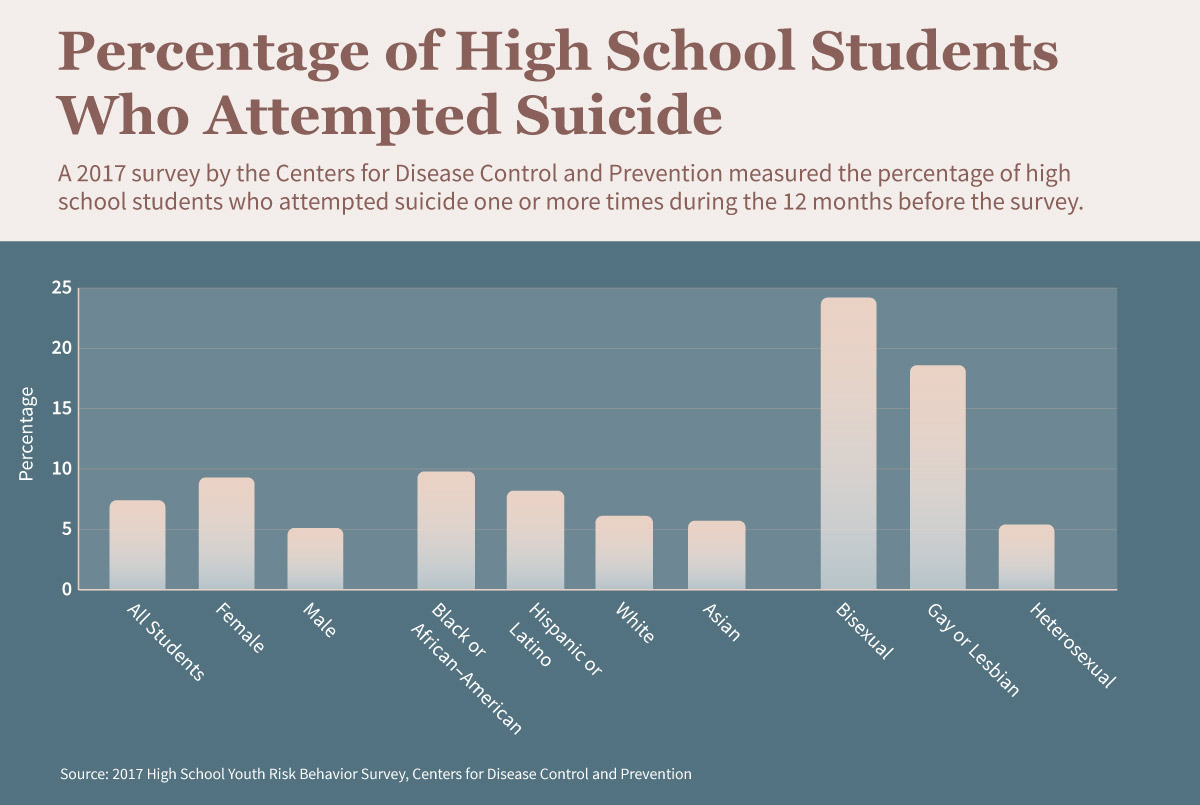

A 2017 survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 7.4 percent of high school students attempted suicide in the 12 months before the survey was taken. The percentage was more than triple (24.2) for bisexual students and double (18.6) for gay and lesbian students

Young people are typically “unable to see beyond their acute and immediate struggles, which may be related to being victimized by a bully, being a survivor of sexual assault or violence, being uncertain about their sexual orientation, or medical and/or psychological disorders,” said Krystle Herbert, LMFT, PsyD, a psychology adjunct faculty member for the online master’s in marriage and family therapy program at Pepperdine University.

But experts say that with the right type of support from health care providers and parents, a child and their family can get the tools to move forward in life and avert future mental health crises. Other family members, friends, health professionals, and educators can be a vital part of a child’s support team, too.

However, every family’s experience in the days, weeks, and months following a child’s suicide attempt is different. There’s no single plan of care to offer parents after such an event, said Kristi Phillips, PsyD, LP, a licensed clinical psychologist with the Department of Psychology and Psychiatry at Carris Health in rural Litchfield, Minnesota. But there are health care options, behaviors, and word choices parents can employ to support their child and improve family communication.

Ensuring a Safe Return Home

Immediately after an attempt, parents can bring their child to an emergency room or call an ambulance or local crisis center. ER doctors might admit a child to the hospital for medical care, or to a psychiatric hospital or program—if there’s one nearby—where the child can be monitored and receive mental health counseling and medication.

When a child is discharged, they’ll receive a plan that often includes a recommendation for outpatient counseling. If a parent has any concerns at this time, they should talk with their child’s medical team to clarify plan details.

“Advocate for the needs of your child, especially if they do not appear ready to reenter the home and back into their prior routine,” Herbert advised.

Once home, Hebert says children should step down to an appropriate level of care based on symptom presentation. This is not always traditional outpatient psychotherapy with an individual therapist. It may include more structured environments such as a residential facility, partial hospitalization, or intensive outpatient care, all of which utilize a multidisciplinary team of medical and psychological professionals to create a treatment plan usually made up of groups, individual therapy, medication management, nutrition counseling, or other needs on a customized plan.

Treatment can range from weekly to several times a week, Phillips said. Children sleep at home but spend some or most of their waking hours at the outpatient center receiving individual and group counseling and participating in activities, such as mindfulness exercises, yoga, acupressure, acupuncture, journaling, and other strategies and techniques to manage their mental health.

Community crisis centers, churches, and other religious organizations may also be helpful, especially if families don’t have the money or health insurance for outpatient care or private therapy, said Joel Dvoskin, PhD, a licensed clinical psychologist in Tucson, Arizona, who specializes in assessing and managing suicide risk. Religious leaders often receive family counseling and mental health training, he said. Parents can also ask their doctor or pediatric hospital about telepsychiatry and other telehealth options for mental health counseling.

After leaving the hospital, parents should also actively work with their child or teen’s mental health care team to develop a safety plan, Herbert said. That team might include a psychiatrist, psychologist, pediatrician, and/or school counselor. Phillips advises parents to identify their child’s “triggers,” such as relationship or academic stress, the anniversary of a loss, and alcohol and other substances they’ve used, and strategies on how to diffuse those stressors.

How to Create a Mental Health Safety

Plan for Your Child

When a child is discharged from the hospital or psychiatric hospital after a suicide attempt, their medical team will provide a care plan. Parents and mental health providers can also help children develop a safety plan—a go-to resource for when they feel stressed, need additional support, or are in crisis mode. A safety plan, sometimes called a Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP), can include:

- A list of your child’s “triggers.”

- Early warning signs that might suggest your child is feeling sad or stressed before those emotions become overwhelming.

- A list of trustworthy, non-judgmental family members and friends to be called upon during periods of stress or crisis.

- Relaxation exercises and stress reduction techniques.

- Affirming words and activities to remind your child of their positive qualities.

- Reminders and tips to eat healthfully, exercise, and sleep.

- A list of people and organizations not to call to avoid further stressing out your child.

- Who to call (911, local crisis center, suicide prevention hotline, your child’s therapist or pediatrician) and where to take your child for medical help in a crisis.

Sources: Krystle Herbert, LMFT, PsyD.; Joel Dvoskin, PhD; Kristi Phillips, PsyD, LP; Tammi Ginsberg, LCPC; Dese’Rae L. Stage, LiveThroughThis.org; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; HealthyChildren.org ; SAMHSA .

Understanding Your Emotions after Your Child’s Suicide Attempt

For parents, a child’s suicide attempt can spark a host of emotions, said Tammi Ginsberg, LCPC, a licensed therapist and board president of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

“A parent might feel shock, guilt, anger, embarrassment—a multitude of things,” Ginsberg said.

This emotional rollercoaster isn’t unusual. Herbert points out that family members are working to manage the feelings of the individual who attempted suicide and to ensure that they obtain the necessary resources to prevent future occurrences, while simultaneously working through their own grief process.

“This is an arduous process and more often than not, the parents do not have a background in psychology and may not be savvy in navigating the complexities of the mental health system,” said Herbert. “They may even be combatted with indirect accusations of poor parenting practices by family, friends, and even mental health professionals.”

Emotional Toll on Family Members

Parents and other family members may experience the difficulties listed below after a child tries to take their own life. If so, they should consider seeking out their own therapy.

- Feeling on edge or being easily startled.

- Difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, and waking early or sleeping too much.

- Nightmares or flashbacks about their child/teen’s suicide attempt.

- Difficulty concentrating or paying attention at work or in general.

- Carelessness while performing routine tasks or forgetting tasks altogether.

- Outbursts of anger, sometimes with no apparent reason.

- Family or work conflicts not experienced before their child/adolescent made a suicide attempt.

- Experiencing fatigue.

- Feeling numb or in a daze.

- Excessive anxiety about personal safety or the personal safety of others.

- Feelings of being especially alone.

- Feelings of depression, loss, sadness, and anxiety.

- Feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and lack of control.

Sources: Krystle Herbert, LMFT, PsyD; Joel Dvoskin, PhD; Kristi Phillips, PsyD, LP; Tammi Ginsberg, LCPC; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; SuicidePreventionLifeline.org ; The Washington Post.

Mental health experts caution against being judgmental or angry with a child who’s attempted suicide.

“If there’s anger, get over the anger quickly because you don’t want to increase your child’s pain or despair by screaming at them. There’s nothing about rage that prevents suicide,” Dvoskin said.

He encourages parents to focus on supporting their child and listening more than talking.

Parents may be tempted to hover near their child or teen because they’re afraid the child may attempt suicide again. It’s a valid concern.

“Many of those who attempt suicide, go on to complete suicide in the future if they do not have proper supports,” said Herbert.

One recent study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry noted that a suicide attempt may be an even “more lethal risk factor for completed suicide than previously thought.”

Younger age and alcohol use are also risk factors for attempting suicide again, according to research in BMC Psychiatry. Research has also shown that half the people who die by suicide, and two-thirds of people who attempt suicide, received a mental health diagnosis or treatment in the previous year, according to a study in The American Journal of Psychiatry.

But once a parent and their mental health providers have agreed a child or teen doesn’t need 24/7 observation, shadowing them may be stressful for them and for any parent, Dvoskin said. The goal is to find a balance between respecting their personal space and privacy, especially a teen’s, while looking out for their mental and physical well-being. Be straightforward but empathetic, he advises.

“Ask them, ‘Are you thinking of hurting yourself? Should I be scared for your safety?’ There are plenty of respectful ways to ask,” Dvoskin said. But he cautions that if they are using language that suggests they are thinking about another attempt, such as, “I want to die,” stay with them until you can get medical help.

“People can be afraid to ask that question because they don’t want to put that in someone’s mind, but [asking about suicide] doesn’t increase the risk of suicide, and that’s based on research ,” 1 Ginsberg said. “So, the best thing you can do is be present. Be aware. Talk. Suggest.”

Ginsberg also recommends looking at your house through a lens of safety. Keep all medication locked up and toss unused drugs that could be abused. Secure firearms, car keys, sharp instruments, ropes, and poisons. A suicide attempt is often impulsive—a moment of despair that’s really a cry for help—but a loaded gun is final, she said.

Communicating with Your Child or Teen after a Suicide Attempt

Parents are a child’s best hope and they need to be able to trust you. Be honest when they have a question about life and try to understand their worldview. Ask them questions and listen with respect.

Phrases to Express Support

- Whenever you want to talk, I’m here to listen and support you.

- I won’t judge, and I’ll never stop supporting you, no matter what challenges you face.

- How are you feeling? I’ve noticed you’re (sad, angry, or acting out more).

- Are you thinking of hurting yourself? Should I be concerned for your safety?

- I love you.

- I’ll be here for you no matter what.

- My love is unconditional.

- I had no idea you were in that much pain.

- I’ll get you the help you need to get through this challenging time or tell me how I can help.

- It’s my No. 1 job as your parent to keep you alive and well.

- Talk to me, I want to hear what you have to say.

- Healing is a process and takes time.

Actions to Aid in Healing

- Practice positive affirmations every day, such as, “I am enough. I am unique.”

- Remind them that it’s OK to not be OK.

- Help them develop positive coping skills, such as exercising regularly and other stress-reducing techniques, and encourage them to surround themselves with positive friends.

- Help them write a list of their best features: physically, mentally, and socially.

- Encourage them to keep a journal of their feelings, experiences or anything else they want to write about. Drawing, praying, and listening to music can be positive coping skills, too.

- With the help of a professional, try to understand what led them to their suicide attempt — for example, depression, bullying, sexual identity issues, or a more situational issue such as a break-up.

- Talk with a mental health counselor if they are having trouble opening up to you, and realize they may want to talk even if they say they don’t.

Sources: Krystle Herbert, LMFT, PsyD; Joel Dvoskin, PhD; Kristi Phillips, PsyD, LP; Tammi Ginsberg, LCPC; Dese’Rae L. Stage, LiveThroughThis.org; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention; SuicidePreventionLifeline.org; HealthyChildren.org.

Getting Back to ‘Regular Life’

Parents, other family members, and the child who has attempted suicide may find it difficult to communicate with friends, curious classmates, concerned teachers, and nosy neighbors once they return to home and school.

Herbert says the first step families should take when deciding what to communicate is to ask the child how they feel about sharing the attempt with loved ones.

“It is important to frame that it may be helpful to bring others into the conversation to be additional provisions of support and to reassure family and friends that may have been worried or anxious about the child,” said Herbert.

Act as advocates, she says, and remind children that they don’t have to share anything that they feel uncomfortable sharing.

To help relieve the stress of explaining to others what happened, Phillips recommends talking with children about how they will respond to questions people may have. Parents, siblings, and the child can practice explanations of why they have been away. A psychologist or mental health provider can assist with techniques and strategies.

One technique: Tell a nosy neighbor, “We are dealing with family concerns” as a way of ending the conversation. Another approach: Thank a classmate for their concern, and say, “We are only talking with our closest friends about this personal issue.”

And while privacy is to be valued, sharing and communicating can be a healing experience for a child or teen who has attempted suicide.

“It is important that this is their story to tell and they feel that they have control over how it is told, with whom and when they feel comfortable,” Phillips said. “That said, I have had many patients share how important it is to feel emotionally connected to peers and other supportive communities while they are managing their mental health after a suicide attempt.”

Families who have been affected by suicide attempts can support one another by being available and sharing their individual stories of grief. They can also seek out other families going through the same issues by joining support groups in their local communities and online.

Talking about mental health also destigmatizes suicide attempts, Ginsberg said, explaining that it can help children understand the brain may sometimes need treatment just like an injured leg or arm.

Throughout the entire experience, parents and family members shouldn’t forget about themselves, Herbert adds. Compassion fatigue can set in when taking care of a person who has attempted suicide. Both the child and the family members need to understand that healing is a process and takes time.

“You cannot pour from an empty cup,” said Herbert. “Allow yourselves the opportunity to grow and heal without timelines and expectations.”

If you or someone you know is thinking about or has attempted suicide and needs help, consider reaching out to the following organizations:

Source: 1. Dazzi T., Gribble R., Wessely S., Fear NT. “Does Asking About Suicide and Related Behaviours Induce Suicidal Ideation? What Is the Evidence?” Psychological Medicine, December 2014.

The following section includes tabular data from the data visualization in the post.

Percentage of High School Students Who Attempted Suicide↑

| Demographic Category | Percent |

|---|---|

Female | 9.3 |

Male | 5.1 |

Black or African-American | 9.8 |

Hispanic or Latino | 8.2 |

White | 6.1 |

Asian | 5.7 |

Bisexual | 24.2 |

Gay and Lesbian | 18.6 |

Heterosexual | 5.4 |

All Students | 7.4 |

Statistics represent students who attempted suicide one or more times during the 12 months before the 2017 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Citation for this content: OnlinePsychology@Pepperdine, the online clinical psychology master’s program from Pepperdine University.